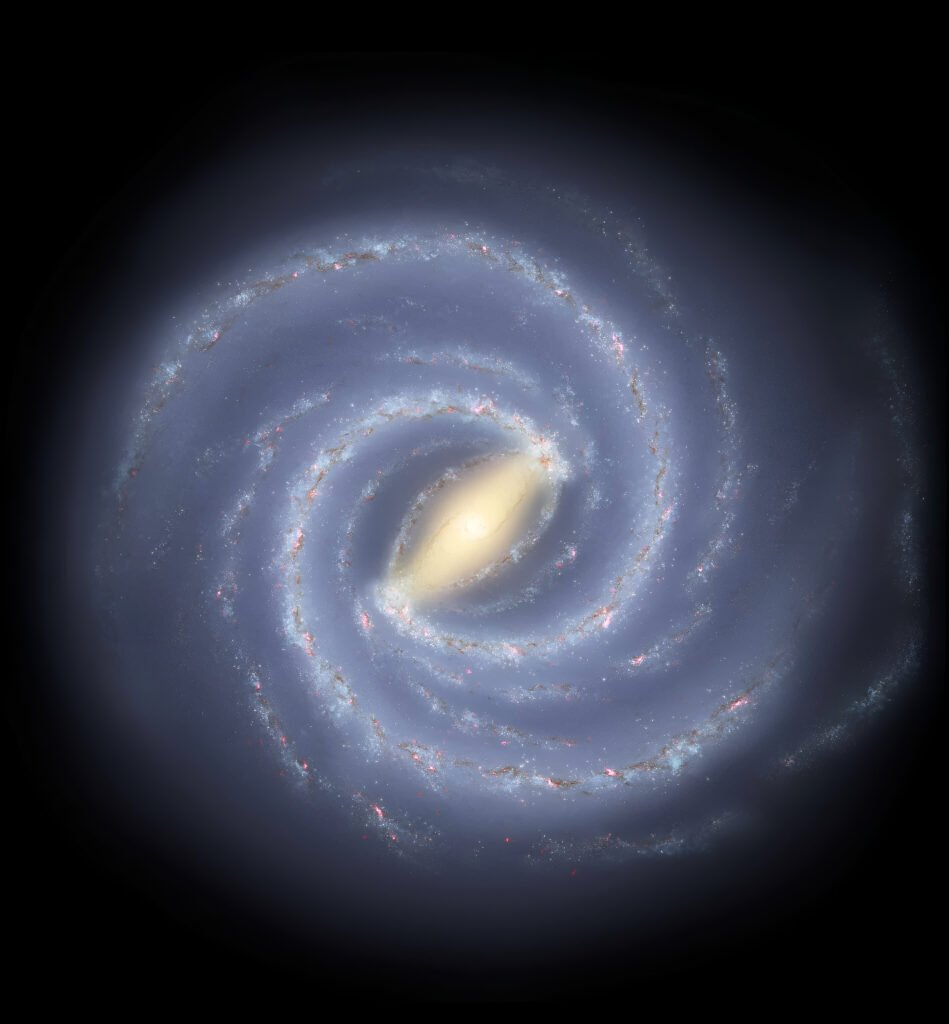

The cosmos just handed astronomers another surprise—one that could change how we understand the formation of galaxies in the early Universe. Scientists have discovered a massive, well-organized spiral galaxy that looks astonishingly similar to our own Milky Way, despite having formed just 2.6 billion years after the Big Bang. This galaxy, J0107a, is not only wonderfully formed but also has a stable galactic bar, a characteristic more often found in much older, more developed galaxies.

Let’s delve into what makes this find both exciting and mystifying for astronomers.

A Galaxy Far Away… and Way Too Mature?

J0107a is not the earliest spiral galaxy discovered from the dawn of time, but it’s by far the most impressive. Located billions of light-years from us, it has a mass of 450 billion solar masses and creates stars at a rate of 500 solar masses per year. That’s about 100 times faster than our own galaxy’s rate.

What’s more remarkable? This galaxy already has a central galactic bar—a straight, luminous feature made of stars and gas that stretches across its center. In the Milky Way and other mature spiral galaxies, bars act like engines, funneling gas inward to trigger star formation in the galactic core. But to find such a well-organized shape in one of the early universe’s galaxies is unexpected. Extremely unexpected.

Rewriting the Rules of Cosmic Evolution

Traditional models of galaxy evolution indicate that the universe was a mess in the early days. Galaxies were meant to begin small, and they accumulated stars over time as gas coalesced around an initial black hole core. Through billions of years, interactions and mergers with other galaxies would cause them to expand and arrange into spiral forms.

But J0107a appears to bypass a few evolutionary steps. According to Shuo Huang of the National Astronomical Observatory of Japan, who led the research, this galaxy’s structure and behavior are strikingly similar to those of galaxies we observe in the local Universe today. It’s as if someone fast-forwarded the evolutionary clock.

“We proposed ALMA observations to see whether the bar of J0107a is channeling gas inward to feed the central starburst,” Huang told Science Alert. “But we did not expect the gas distribution and motion to resemble present-day galaxies so closely.”

A Star-Making Powerhouse

Using data from the James Webb Space Telescope (JWST) and the Atacama Large Millimeter/submillimeter Array (ALMA), Huang’s team mapped how gas flows within J0107a. What they found was astonishing: the bar is channeling gas to the center of the galaxy at a rate of 600 solar masses per year.

This inflow of gas creates dense clouds, which are perfect conditions for the birth of new stars. In fact, the star formation rate in J0107a is 10 to 100 times higher than what we observe in similar galaxies around us. This suggests that galactic bars may have played a major role in driving early star formation, much earlier than scientists previously believed.

An Uninterrupted Life?

One of the more baffling aspects of J0107a is how stable it seems. Galactic bars are fragile. Even minor interactions with other galaxies can distort or disrupt them. Yet this galaxy’s bar is thriving, implying that it hasn’t had any major disturbances. That leads scientists to believe J0107a may have formed rapidly from cold gas streaming in from the cosmic web—an enormous network of intergalactic gas filaments that crisscross the universe.

“How the cosmic gas stream arrives in the galaxy and settles down to make a disk is an open question in observational astronomy,” Huang said. “The theoretical predictions have not been directly observed yet.”

Raising More Questions Than Answers

While the discovery of J0107a answers some questions about the capabilities of early galaxies, it opens up many more. For example, is the process of star formation the same when gas is much denser than in today’s galaxies? If not, are we missing a whole set of rules about how stars and galaxies formed in the early universe?

Also, if one galaxy like J0107a exists, are there more out there, hiding in plain sight, reshaping our understanding of the early cosmos?

A Window Into the Past—and the Future

J0107a is more than just an early-universe curiosity. It’s a reminder of how much we still have to learn about the cosmos. As telescopes like JWST and ALMA continue to reveal the distant corners of the universe with unprecedented clarity, we can expect more discoveries that challenge long-standing theories.

In the meantime, astronomers will keep observing J0107a, hoping to unlock the secrets of its rapid growth and uncanny resemblance to our Milky Way. As Huang’s team continues their work, one thing is clear: the universe is much more efficient—and much more mysterious—than we ever imagined.